Link to Family Tree to understand family relationships.

Warning: today’s post may be difficult to read.

In yesterday’s post, I described the most recent part of my journey to learn more about my family, particularly about my grandfather Vitali. Perhaps some of the information has not wanted to be found until quite recently. Or perhaps I wasn’t ready to find it.

Only by searching in the right source at the right time have I been able to get answers to questions, some of which I thought might never be answered. Perhaps a particular document has only recently been digitized or uploaded, or perhaps it’s the luck of the search. My search has certainly been easier than it was for my grandmother and the thousands of people looking for traces of their loved ones at the end of World War II.

This summer I decided to look for information about Vitali at the Arolsen Archives in Germany. I had searched there in the past and found nothing. As I mentioned in the July 5 post, I found several items related to Vitali’s time at Buchenwald, including what may have been the original document that said that Vitali had been seen at the time of liberation – the statement that encouraged Helene and her children to believe that Vitali had survived (helped also by her friend Paula’s letters assuring her that she’d seen and heard from him).

Häftlings-Personal-Karte, Haim Cohen, Buchenwald p. 2; ITS Digital Archive, Arolsen Archives; https://collections.arolsen-archives.org/G/SIMS/01010503/0273/52439235/002.jpg

Handwritten statement: “This person appears on lists of liberated prisoners (compiled by the American Army)”

Most of the documents were intake and other official cards, with information about him and the belongings he brought with him to Buchenwald. The document below (which is the front side of the image above) sent a shock wave through me and it took several days to recover. Having an intellectual sense of my grandfather as a prisoner was very different from seeing photos.

Häftlings-Personal-Karte, Haim Cohen, Buchenwald p.1; ITS Digital Archive, Arolsen Archives; https://collections.arolsen-archives.org/G/SIMS/01010503/0273/52439235/001.jpg

In early August, when I went back into the Arolsen Archives, I found additional documents, including one that answers the question of Vitali’s fate – that he died on a “death march” near Penting, Germany. When I first spoke to historian Corry Guttstadt in late 2017, this was her theory –tens of thousands of men were marched out of Buchenwald in early April 1945 when the German SS realized they were losing the war. Few prisoners on the marches survived.

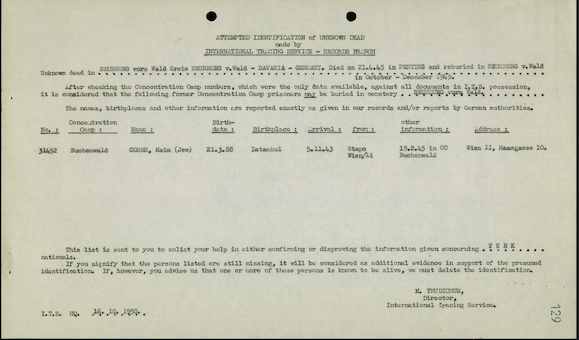

Investigations regarding the sites Neunburg vorm Wald - Rötz. DE ITS 5.3.2 Tote 29; Attempted Identification of Unknown Dead, https://collections.arolsen-archives.org/H/Child%20Tracing%20Branch%20General%20Documents/General%20Documents/05050000/aa/ao/pl/001.jpg

The document states that Haim Cohen was among the unknown dead who were buried in Penting on April 21, 1945 and were reburied in Neunburg v. Wald in the fall of 1949. He was deemed to be one of the buried based on his prisoner number.

Although the above document was created in 1950, it was never found during the many times my grandmother requested information about her husband.

It appears that Vitali died on April 21, about 165 miles away from Buchenwald. The map below shows the distance between Buchenwald and Penting. Also on the map is Flossenbürg – the only reference to Penting I could find said that the prisoners who were in Penting had come from Flossenbürg concentration camp. It would make sense that they would believe that Vitali had been with the group from Flossenbürg since it was on the way from Buchenwald to Penting.

All of my life, I knew that all four of my grandparents had been interned in concentration camps. My grandmother Helene was the only grandparent I ever met. It was comforting to think that Vitali might one day fulfill his wife’s and children’s hopes that he would show up on their doorstep.

For most of my life, I avoided reading books and watching films about the Holocaust – I never felt I “needed to” learn about the specifics because I had internalized the loss and trauma and didn’t feel the need to gain more understanding or empathy. It’s taken me until now to be able to look more closely – poring over my grandmother’s letters and stories, and looking until I finally found what happened to Vitali. Over the past few weeks I have felt sad and anxious and sick. It has taken me many days to sit down and write this post. Last week, I arranged to meet with my translator to look at some of the Buchenwald documents before writing today’s post, and conveniently “forgot” to hit send so she was not able to look at them in time. But they really need little translation.

When Corry and I spoke about discovering Vitali’s fate, she hoped that I would feel a sense of closure, that I would feel better no longer wondering why he never contacted his family if he survived. At this point, I guess it’s good to know that he didn’t desert his family. Still, it’s hard to let go of the dream my family held for so long and accept that the life of this smart, resourceful man was cut short in this awful way.

I’m glad that at the same time that I was discovering evidence of Vitali’s death, I found more information about his life in Vienna through newspaper articles (see yesterday’s post). He was much more than a victim or a statistic.

After learning about Vitali’s fate, I began thinking about my grandmother’s time in Istanbul. She arrived there in April 1945, about the time Vitali would have been marched out of Buchenwald. She remained in Istanbul for an entire year, boarding the SS Vulcania on April 14, 1946 and arriving in the U.S. on April 26. The Jewish period of mourning is twelve months. Unknowingly, my grandmother spent the entire year after Vitali’s death in his birthplace. There seems something sadly poetic about that.