Link to Family Tree to understand family relationships.

The real nightmare begins

Life in Vienna became virtually intolerable for Jews by the late 1930s. Helene and Vitali remained there until late 1943 when Germany arrested Turkish citizens and those of other countries who had been allowed up until that time to remain. If their native countries did not repatriate their citizens, these people were deported to the death camps just as German citizens and those of annexed countries had been.

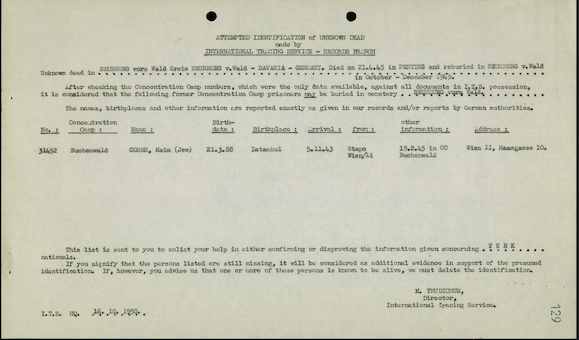

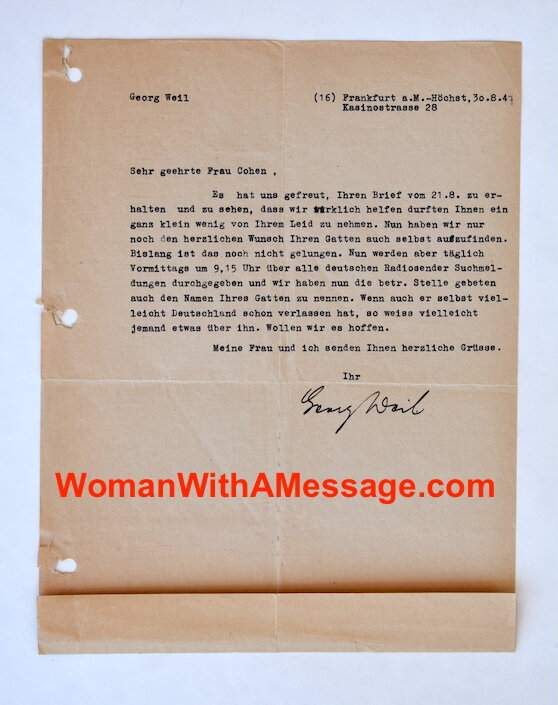

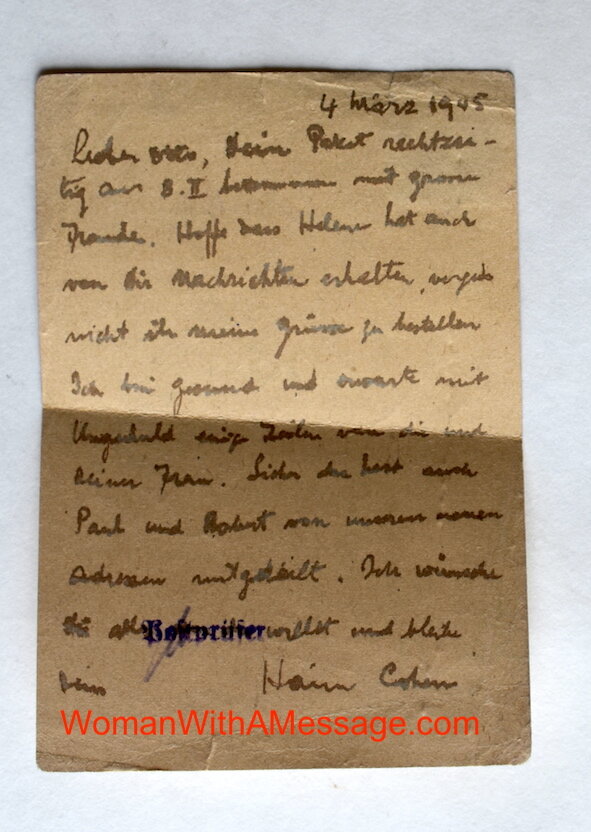

Despite the humor and affection, Helene’s letters to her children from 1939-1941 give us a vivid picture of the difficult times they lived in – food and heat were in scarce supply. They were not allowed to earn money at the same time as costs skyrocketed. Every attempt to escape Vienna was thwarted by bureaucracy and rule changes. Helene wrote about the times leading up to and including their arrest in the October 15 post. On November 5, 1943, she and Vitali arrived at their respective hells: Ravensbrück and Buchenwald. As we learned in the August 24 post, Vitali did not survive the war.

Germany kept meticulous records and today we see paperwork from Helene and Vitali’s registration into each camp.