Link to Family Tree to understand family relationships.

With no letter today, we have another story by Helene, likely written in San Francisco in the 1950s.

When I sorted through my family papers, I found several stories my grandmother had written about her childhood. One was written in German and called “Der Loewe von Bilin.” Having a little knowledge of a language is sometimes less helpful than having none at all. I decided that the title referred to my grandmother’s maiden name Löwy and that the story would tell me all about her family and life in the Bohemian town of Bilin where she was born. Therefore, I asked my friend and translator Roslyn to prioritize its translation.

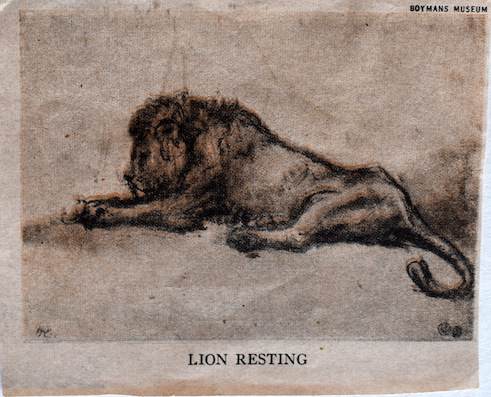

As I soon learned, the title of the story is “The Lion of Bilin” and refers to the name of the mountain that overlooked the town. When Roslyn translated this story in early 2018, I was really disappointed that it was mostly about people unrelated to her and I set it aside and did not read it again until recently. I wasn’t yet familiar with her writing style, and had not read enough of her childhood stories to understand that she felt completely out of place in Bilin as a child. Like “O Katherina” which we saw on March 13, in this story Helene takes us on a wonderful journey, this time from the 1890s in Bilin to 1918 in Vienna, and we learn a lot about her childhood as well as her attitudes and life before she met Vitali. As often is the case in her stories and letters, Goethe makes an important appearance. You can see drawings Goethe made of Bilin at the Goethezeitportal. Images 19-22 are of Bilin.

I have one stand-alone copy of this story which looks like a final draft. In a binder with other childhood stories, she had an earlier draft as well as images of a lion and of the mountain.

Final draft of story

Earlier draft

The Lion of Bilin

by Helene Cohen

Borschen Mountain is located in a valley between the Erz Mountains – the natural border between the Empires of Saxony and Bohemia – and the Bohemian Uplands. It is 538 meters above sea level. It is the highest clinkstone rock cliff in the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy.

We had learned this in the ‘90s in geography class. We had to memorize it. However, what was far more interesting to us pupils than the height above sea level of this unforested basalt rock were the many tales and stories about our local rock. The northern Erz mountain chain, with its mountains more than 1000 meters high, the very old, gigantic, tall evergreen forests, the unforgiving snowstorms in the winter and the menacing storms in the summer, impressed us greatly. The moods of this climate made the wild, fantastic tales seem so much more believable to us than what we learned about the Borschen, which just stood there doing nothing, splendid in its isolation, quiet and evoking no fear. It took in the sun and let it be reflected by its glittering white quartz. Often enough, however, it just looked gray. But the mountain, which in its quiet majesty looked down confidently and even arrogantly on our little medieval city, could not be trusted. Tourists unfamiliar with the area might have had a hard time visiting this rock, even though they had heard of its very interesting flora and its rare minerals. They might have seen our little Cinderella-esque city in the Bohemian spa region, but there was no sign that might have told them how to go up the cliff safely. It is not generally known that Goethe, in his role as a nature researcher and artist, visited Bilin during his stay in Teplitz. Fascinated by this odd Alpine formation, he drew a sketch, and, struck by the odd mood of nature, he called it The Lion of Bilin. What a great wonder that Napoleon, on his way to Austerlitz, was thinking of other matters. Otherwise, he might have had the Borschen removed and installed somewhere in France. Whoever travels on the dusty rural road which passes by the Bohemian Sphinx could not have believed that the bushes between the rifts and chasms was actually a clever camouflage, a trap to prevent the eradication of the rare grasses found there along with the Borschen carnation.

Postcard in binder with draft of the story

Drawing in binder with draft of the story

We, the school children, knew nothing of this. To us, the Borschen was not a lion, and was of no geological or botanical interest. It was just a splendid place to play hide and go seek, and (cops and) robber games. Later, much later, I deeply regretted having been such an obedient child who stayed away from the group who, even just in play, wanted to harm the Borschen region.

Two boys, the brightest but also the wildest in their class, were the ringleaders. Their names were Ottl Kurz and Attl (Arthur) Kurz. (The last name means “short”). They were the smallest kids around, but they were such daring rascals that older, bigger kids respected them. The Kurz boys’ boldness seemed more important than the ten to fifteen centimeters in height that the older boys had on them. While the other boys saw what a great place the Borschen area was for their robber and war games, the Kurz pair were absolutely bewitched by it. They knew every nook and cranny. If the Borschen had attracted a wider audience, they would have made fine tour guides. But that never happened, and so the Borschen remained the favored place of these children, even as they grew older. Later, as university students, they would hike up there with their textbooks, still feeling some kind of magnetic attraction to the place, as a criminal often feels drawn to the scene of his crime. They always went to this place, even though it could have been disastrous for them. But I’m getting ahead of myself.

During summer vacation, Ottl and Attl Kurz left the house at 6 a.m. to go to their Borschen, which always had something new to show them, like in the Thousand and One Nights.

These boys’ parents were used to these escapades, and did not worry when their roguish boys – whom they impersonated at times - came home a bit late from the mountain, hungry as bears. But when it got to be 9 o’clock, and their boys still had not come home, they started to worry. They notified the police, and tired miners and field hands who heard the rumor also joined the search. It’s strange how popular these young rascals were.

The search was only carried out in the immediate area of the Borschen. Searching the forests and the nearby spa was deemed unnecessary. After a two-hour search, aided by the full moon, the boys were found, unconscious and with several holes in their heads, in a deep chasm. They were transported to the hospital on a hay wagon.

At that time, I was no longer in my home town; I lived in Vienna. I heard of the tragedy that had befallen the rascals some twenty years later, when I ran into Engineer Kurz in the revolving door of a Viennese café. We greeted each other, laughing, as if we had just seen each other recently.

“Hi there, HE. Still the same?” The two letters had a double meaning. They were my nickname, but in the Bilin dialect they also meant “crazy”. And Mr. Kurz did intend that double entendre! He grabbed my arm. “Are you expecting someone? Really, you’re not? Then we can sit at the same table.”

“Ottl Kurz, you still haven’t grown up!”

We sat together for several hours, putting everyone down – the locals, the bigwigs. We thought the entire population, including us, was just a bunch of characters. For the first time, I realized that it bothered Otto that he was so short, or at least it had bothered him in his younger days. He told me – and he was lying – that his claustrophobia, which he really did have as a result of the disaster at the Borschen, had made him unfit for military service. He thought he could help the fatherland more by thundering on about war, complaining about the war economy, the victors, and so on. He could disguise his claustrophobia as a mental illness.

I laughed at his humor, but also felt great sympathy due to the insights into his psyche which he had shared with me. I decided to be nice to him and take care of him, even though he kept teasing me. His way of making fun of his own shortcomings was the best type of gallows humor. After the waiter interrupted us, I decided to change the subject:

“Hey, why don’t you tell me about the robber show incident? I wasn’t living at home by then.”

“Yes, it really was quite a while ago; now, our last rascal prank is mentioned in the new editions of school books as a warning about what not to do. Now, 20 years later, I still don’t know how we two got home. We were running around showing off our battle scars, with our heads bandaged. We were particularly excited about being excused from school for a whole year! That alone was worth the whole adventure.

I can still remember, as if it had happened yesterday, what happened to me just before we fell down the chasm. Attl, who was a year younger than I, but a centimeter taller, was the daredevil. He stood up on a sharp pinnacle and, making a megaphone with his hands, hollered to me: “Come on up here, Ottl, and look at all this splendor! Not even Lobkowicz has these specimens in his botanical garden. Come smell the fragrance!” I suffered a crippling panic attack. Such splendor could only be found in a dangerous steep overhang; anywhere else, all the rare flowers would already have been picked. Before I could reach him or even warn him, Attl disappeared without saying a word. I called his name; no answer. Gathering all my strength, I screamed: Attl, I’m counting to three and then I’m coming to get you!

The end? I’m sitting here with HE, drinking, in pleasant company, a brown liquid. The coffee of Saxony in the olden days seemed like nectar in comparison. Now, I live in Vienna, the city of song and love.

Attl lives in Germany. He is the main chemist at a dyehouse in Wuppertal. On a business trip before the war, he met a tall, beautiful woman, fell in love with her, and they are happily married. They have two children who are almost as tall as he is, and he is very proud of this. I am, as you may know, since we have acquaintances in common in Vienna, still in service to the Emperor and the King.

“Why don’t you do as Attl did?”

Well, I had more holes in my head than he did, and maybe that’s why I haven’t been able to make the decision to give up the single life. And you? Why are you still single? Are you really not married yet?

“That’s not going to change.”

When you left our home town, people thought you were a little “he” {crazy]. But you didn’t even fall down the Borschen.

I know people were saying things about me, but not that I was crazy. They were saying I had a screw loose because I went to live in Vienna to work and study. The first worked out: I found a job that suited me, but I didn’t have the time or the money for further studies.

Maybe things will change for you eventually. Sometimes our status changes.

If that was an offer, I’d have to say, we are too similar to attract each other.

Who said anything about attraction?

Too bad there’s no more room for another hole in your head. I’d be glad to make another one for you.

Otto laughed out loud. “That sounds almost encouraging. A dressing down, the kind you almost can taste. Maybe you’ll reconsider.”

If you really want to get married, maybe I can be of help. I have a friend. She’s an unusually charming person, and she likes “originals”. If you come to this coffeehouse again, I’m a regular here, and she is sure to be here, too.

In Spring 1919, I received a picture postcard of Borschen, from my friends Fanny and Otto. They were on their honeymoon. I sent them my congratulations, asking if the Borschen didn’t make the claustrophobia act up.

A second card came: “On a good roadway, we came quite near the place I almost lost my head. Fanny was disappointed not to find a shrine to the famous explorer. She would have liked to marry a famous man. I told her that if I had died and then been carted away from there, then I would have been famous. She assured me that she is happy to be married to a man who isn’t famous; that is better than not being married. The Borschen now has a kiosk that reminds one of the ones in Vienna, but the refreshments are better tasting.

How are you doing – until next time? Don’t be “he”, He. Do what we did.