Link to Family Tree to understand family relationships.

When I think about my family’s journey, I am struck by their optimism and resilience in the face of seemingly impossible circumstances. Wherever they were, they continually thought of their far-off family members with love. When possible, they sent greetings and remembrances. They tried not to worry their loved ones, whatever their situation. They imagined a day when they would be together again.

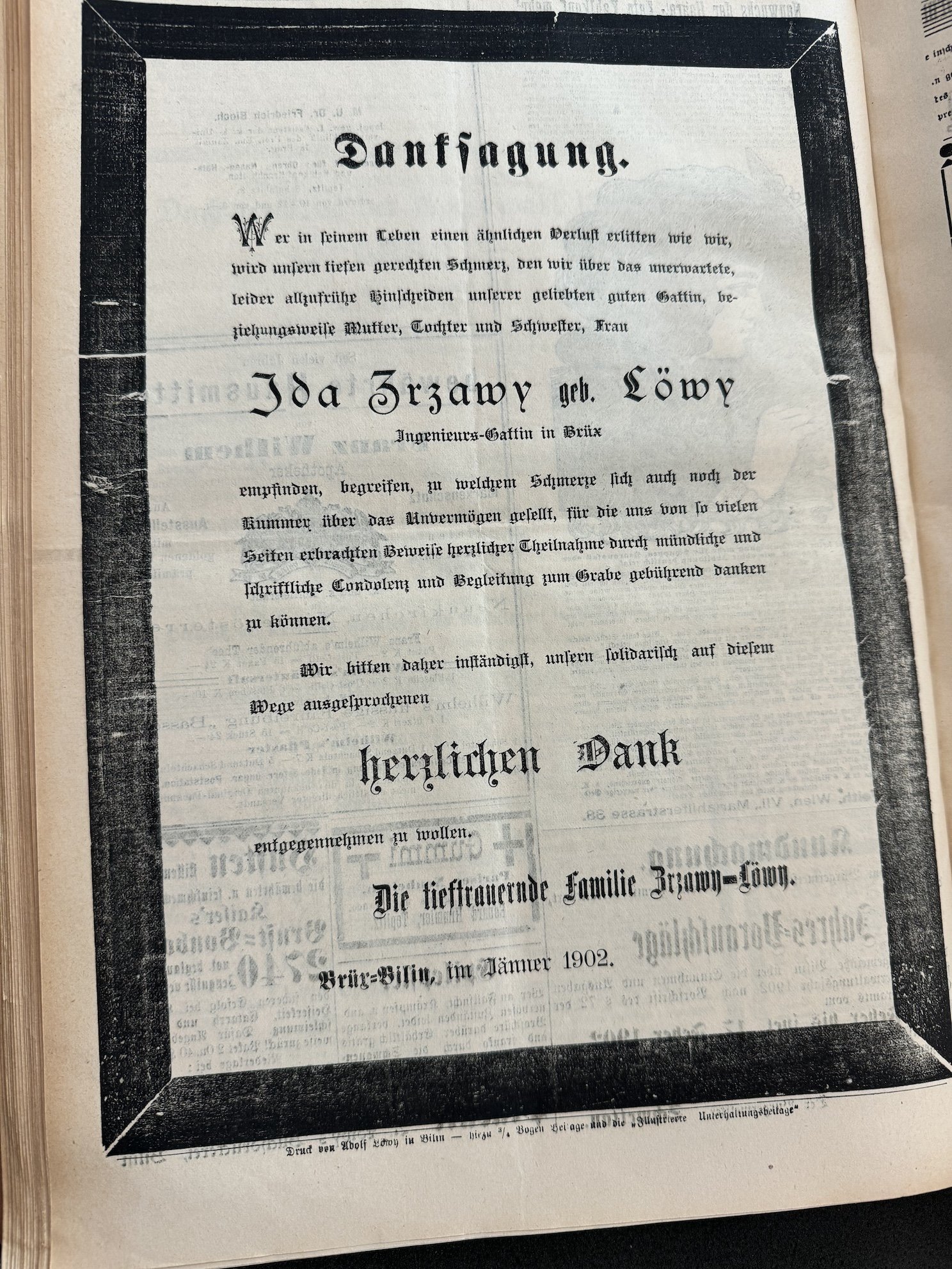

The earliest of my family letters dates from World War I. In 1916, my grandmother’s 18-year-old nephew Erich Zerzawy was spending his first winter as a Russian POW in a camp in Eastern Siberia. Even while requesting letters and packages, in the few words he was allowed he sent wishes for the family’s health and the hope that his brother Robert wouldn’t have to follow his father and brothers into military service.

In December of 1917, Erich’s brother Paul wrote to the family from his post in Romania. He imagined the entire family together at home in Brüx, including my grandmother Helene who would be visiting from Vienna for the holiday. He described his life in the army and wrote individual greetings to each of them. Even from afar, he was eager to find a way to send flour or grain to his family since food was scarce.

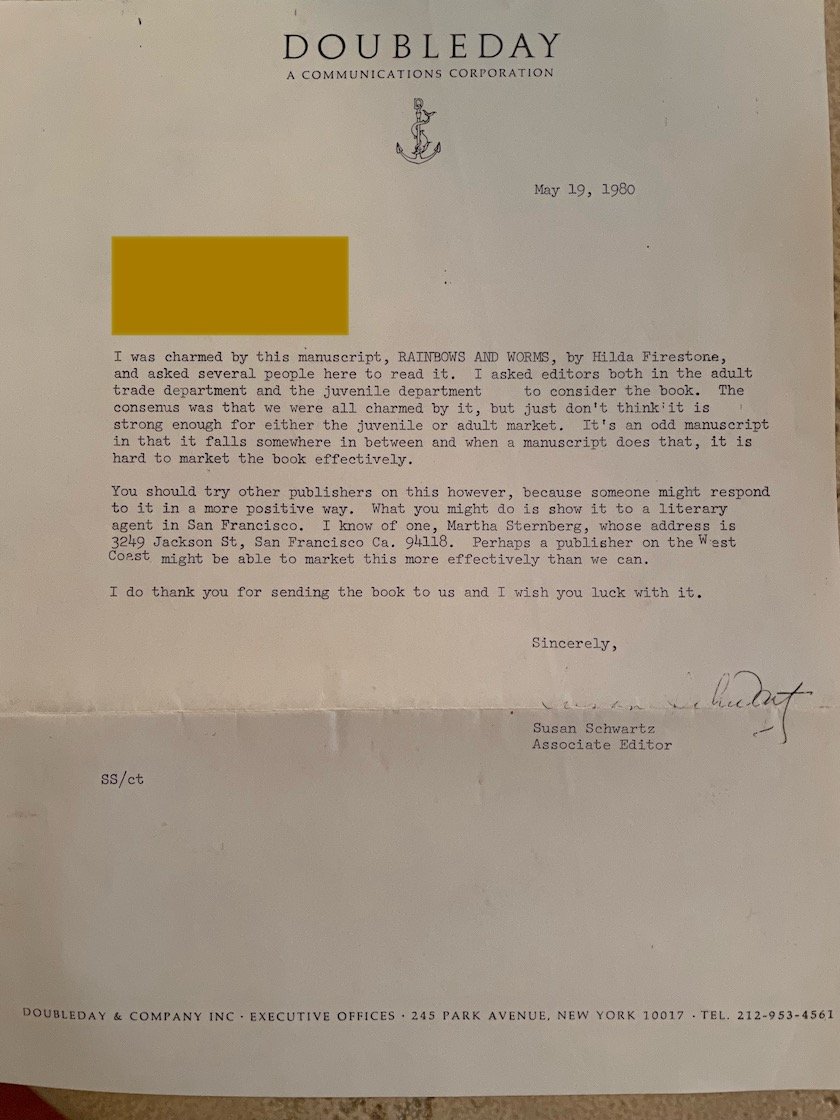

When it was impossible to send birthday gifts, my grandmother wrote letters filled with birthday wishes. In December 1940, she sent her cousin Hilda (with whom her son Harry was living in San Francisco) a song parody about winter in Vienna to the tune of a traditional children’s song.

When Vitali and Helene were trapped in Vienna and unable to send or receive letters, they managed to send a Red Cross letter in 1943 to their children in San Francisco that included birthday greetings within the 25 word maximum they were allowed to write.

Even in the darkest hour, Vitali tried to comfort his wife and children. He was imprisoned in Buchenwald and Helene in Ravensbrück. In a 1944 Red Cross letter to her he wrote: “We will soon see each other again and I delight endlessly in the thought that we can, as before, live together en famille.”

In a letter as a displaced person in Istanbul in January 1946, my grandmother wrote to her children in San Francisco that she hoped to join them soon and that “our European sadness will turn into American happiness and joy.”

Helene, Harry, Eva, and her husband Paul in San Francisco in 1946 experiencing some “American happiness.”

I have always wondered why it was so important to me to celebrate life’s milestones. I found the answer in my family’s letters. No birthday or rite of passage is forgotten. In one of her first letters from Istanbul to her nephew Robert Zerzawy in England, Helene wrote: “The joyful celebration is what I lived for: celebrations of all beliefs, birthdays, all were celebrated joyfully; my children should see only happy faces around them, enjoy music and happiness, eat well and much.” I try to do the same, an honor to her memory.

Helene on her 80th birthday in 1966 with her grandchildren Tim, Jonathan, and Helen - a most joyful celebration!

Over the decades, family members were scattered across the globe in Siberia, Romania, Bohemia, Vienna, San Francisco, Buchenwald and Ravensbrück, Istanbul, and London. Even in the most hopeless of situations, they managed to communicate with family members, not just thinking of themselves but of the welfare of those they loved. I think of their optimism and resilience as I look towards 2025 and the uncertain world we live in. Unlike them, I am home and safe. Like them, I will do what I can to remain hopeful and support and celebrate those I love.