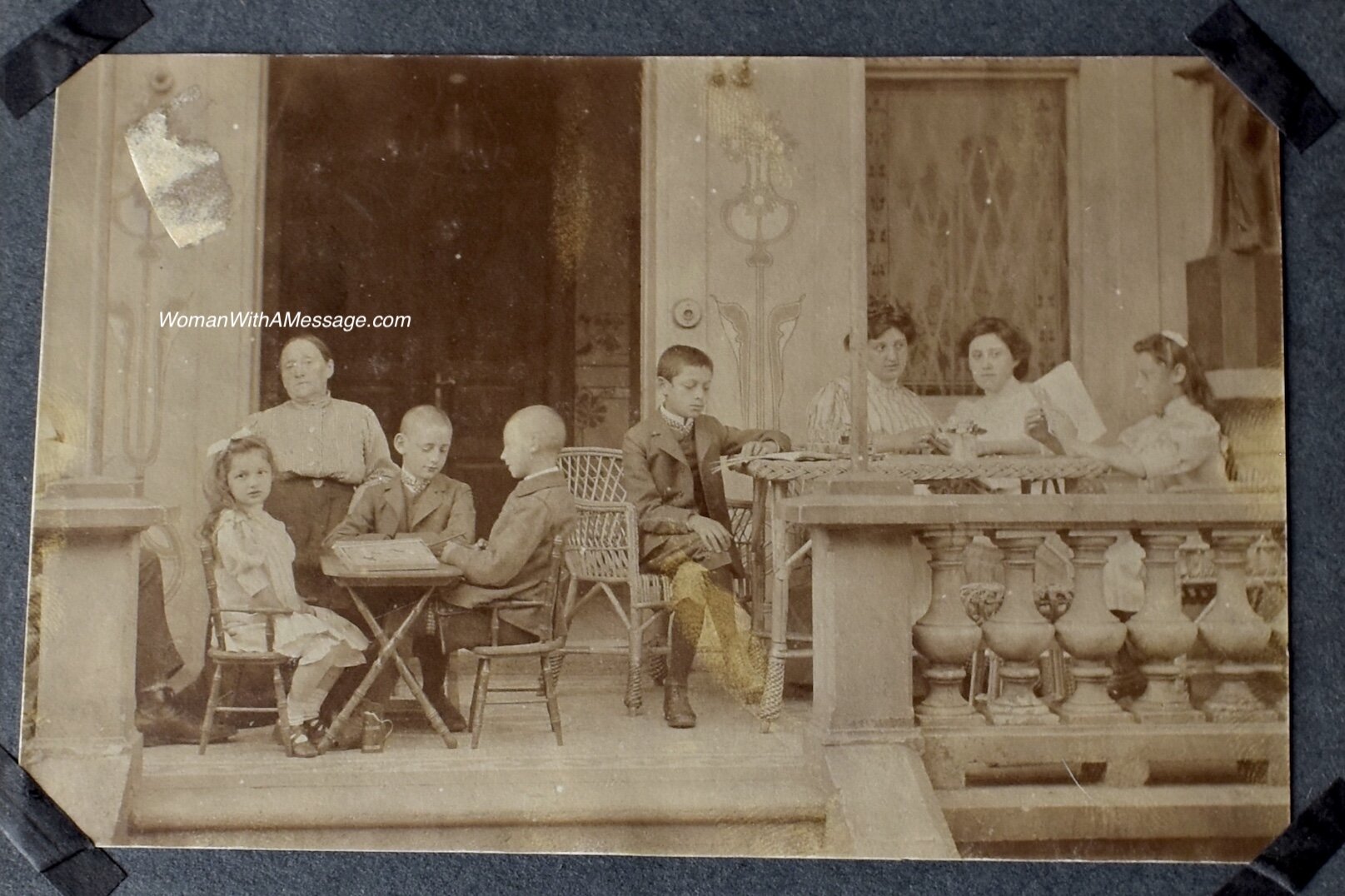

Ida, the oldest of us, came from the veranda next to the kitchen to escape for a while the merciless heat of the sultry August afternoon which was made hotter by her occupation. In general, that sun porch was one of the airiest places in the house and was the most useful space on the floor, serving as storage, sewing and ironing room, as well as the place for reading and writing in daytime. At night it was the our housemaid’s bedroom.

Tired from ironing stiff men’s shirts, collars and cuffs, she entered the drawing-room, seated herself on an easy chair for a half an hour’s rest, and used a handkerchief alternately to wipe or fan her face.

Brother Max and his sisters spent the hot August day each in their own fashion. Max, hidden and smoking behind a host of newspapers, watched Mattl’s strange behavior, sitting with a book in her lap, hands clasped over it, staring vacantly into space. It was not her custom – she normally busied herself with drawing, mending socks or the like, with good humor and humming a melody Ida or he had recently played.

Florly’s sat in her usual seat next to the sewing table before the center-window, watching what was not going on in that deserted main square. She would normally be reading a novel, but that day the unusual sultriness made her drowsy.

Clara sat with Irma and me on the floor, making new dresses for our dolls from her own designs.

A surprising silence prevailed.

Max, still studying his favorite sister’s queer mood, glancing over his paper, diagnosed: Weltschmerz. [world weariness]

“How about a little stroll, Mattl? It is cooler outside.”

“No, I can’t stand the heat either inside or outside.”

“A game of chess?”

“No, thank you.”

To cheer her up, he took his guitar from the wall next to the piano, threw himself into the easy chair again and sang in his agreeable voice:

From paradise I will tell you a new fairy tale

Of an ancient people, but my story is not stale,

Rudiral lalala, rudiral lalala, my story isn’t stale.

The Lord said “hi” to Adam, taking from him

A rib to make yards of Eva, just for his whim.

Rudiral lalala, Rudiral lalala, yards of Eva, for whim.

To Adam he said: “Feel at home, I only beg thee,

Don’t ever take an apple from that tree.

Rudiral lalala, Rudiral lalala, take never an apple from that tree.”

While the Lord with Adam had that conversation,

Eva got acquainted with a snake. What a sensation!

Rudiral lalala, Rudiral lalala, Eva got a sensation.

Pretending to know nothing about,

Took an apple and put it in her Adam’s mouth,

Rudiral lalala, Rudiral lalala, put an apple in her Adam’s mouth. ….

The Lord watching with pleasure his creation’s crown,

Witnessed with fury wicked Adam’s fall down.

Rudiral lalala, Rudiral lalala, witnessed wicked Adam’s fall down.

With rage he called: “Archangel Michael come out.

Expel from paradise Eva and her lout.”

Rudiral lalala, Rudiral lalala, from paradise expel Eva and her lout.

Crestfallen, Adam said, “Eva, that is the end,

I have to go to Halle [not hell: a university-town in Saxonia near the Bohemian border] to become a student.

Rudiral lalala, Rudiral lalala, go to Halle and become a student.”….

“Max, I think you had better not extend your academic liberty to our home. Or do you think it is a proper nursery-song for the kids?”

“Not a bad one at all and very funny, Ida. Besides Hummel is a school girl and Enene will pretty soon become one too and they have to know about religion. By the way, I really had not the intention to intrude in your domain — educational work I leave entirely to you. What I wanted was to chase away was Mattl’s mournful face.”

In order to show Ida that in his opinion the topic was exhausted, he sang another ribald student-song.

“I think,” said Mattl in a better mood, “that second song of Max’s would be a great success for gallivanting Eva.”

Now Ida was really angry. “I think that’s enough, Max: I only hope that one day you will become as outstanding a doctor as you are an unexcelled mountebank.”

Her brother ignored that remark entirely and continued his guitar concert, choosing more vulgar songs.

Florly, who until now had taken no part in that duel of words, dropped her less amusing novel and we children pricked up our ears. Max enjoyed such an appreciative audience and continued with his inexhaustible repertoire.

Ida, who had unsuccessfully tried to calm herself, said: “It is not only the words, Max, but that you corrupt their taste for good music.”

“Don’t be silly. Do you want me to entertain them with Beethoven’s “Lieder an eine ferne Geliebte” [To the Distant Beloved] or Mendelssohn’s “Auf Flügeln des Gesanges” [On the Wings of Song]? Can you not become less moralistic?”

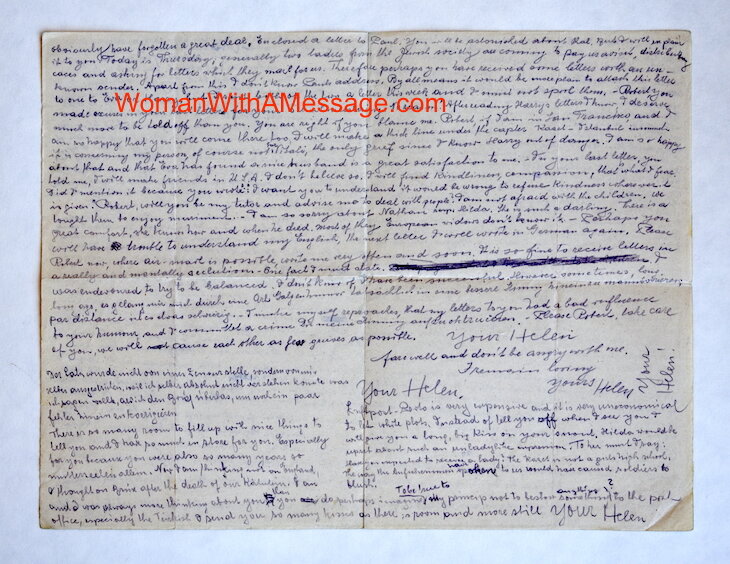

“You can call it moralistic, prudish or spinsterish, I don’t care. It seems to me that you spend more time in the Kneipe (reserved rooms in inns where student associations spent their night singing, drinking, sometimes to the point of rioting) than at the university. I know that your grades couldn’t be better, but your behavior could be. No wonder you fight one duel after another, not considering how upset Mother always is, if by chance she hears about your rowdy exercises from some of your fellow-students who, of course didn’t know that she had no idea of her son’s ‘heroic deeds.’ Your monthly check from Uncle Jack in San Francisco liberally covers your tuition and reasonable expenses. You shouldn’t accept the money Mother gives you, worrying that you do not have enough food to eat. Instead her contributions permit you to live beyond our means. Being the only son doesn’t require you to be a first-rate playboy.”

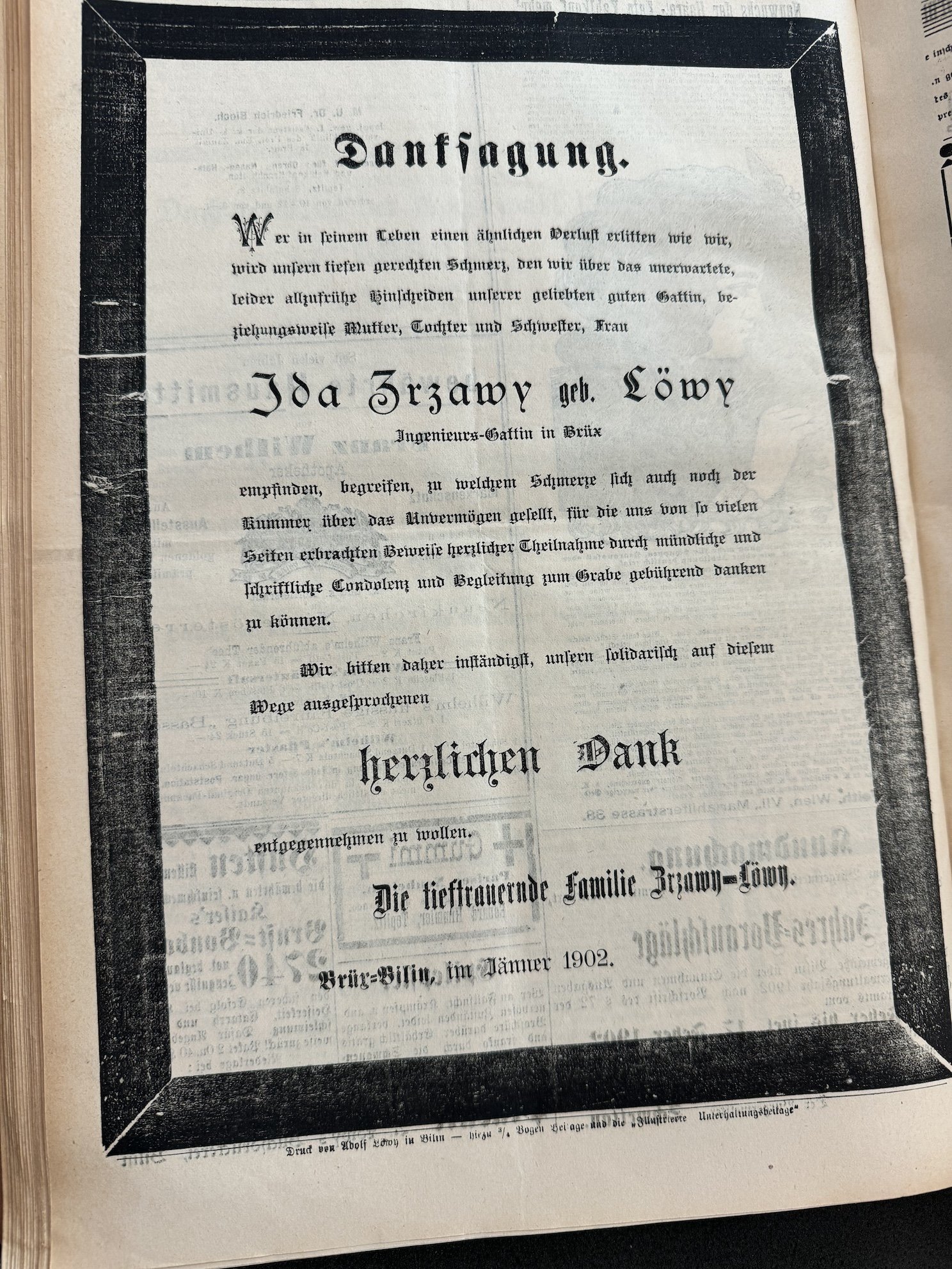

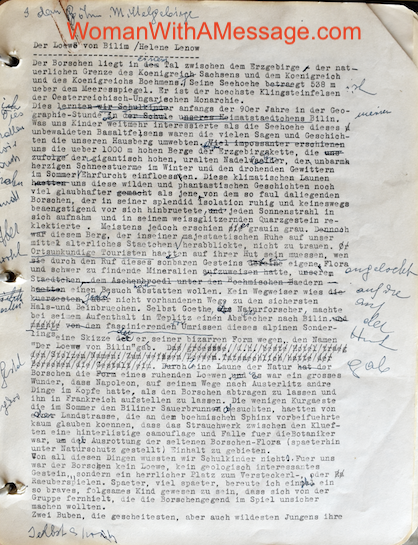

Money affairs were never discussed in our private rooms. Ida, who assisted Father, was up-to-date with the family’s financial situation and mother knew only too well how matters stood, but all the others, including Max, were not interested in Father’s business and were perfectly ignorant about money. We didn’t think money grew on trees, but knew that our parents had a printing and stationery store, that father published a weekly newspaper and sometimes printed some short-lived periodicals. But other than Mother and Ida, we had no idea how much work, trouble, and sometimes losses were involved in Father’s enterprises. Our allowances were given according to our ages and were by no means extravagant. Ida admired Mother’s business routine in the same way she admired her gift for running our household with very limited resources.

Because Ida knew how indifferent we all were to business matters and thinking that we all were engrossed in our activities, for once she forgot her usual circumspection.

Flora dropped her book again and became meditative. Mattl had forgotten her Weltschmerz and listened attentively to Ida’s and Max’s arguments. Clara and Irma didn’t pay any attention, but I cocked my ears. Not that I was interested in their controversy – it was pure satisfaction to me that Ida found fault with my big brother too, unlike Mother and my other sisters who thought him a fearless knight and beyond reproach.

Max felt uncomfortable and wanted to change the subject: “Let us play a sonata.”

“Not now. The air is still contaminated by your Gassenhauers (vulgar songs).”

Flora, Mattl and Clara – who hadn’t taken any part in the battle – interfered now. On that hot afternoon, they enjoyed their brother’s vaudeville humor better than Ida’s austerity.

“Ida,” Florly cut in, “it is ridiculous to make such an issue of a harmless hilarity. I imagine that Halle must be a very pleasant and fascinating place. I have the desire to become a modern Golias too.”

“Goliath, I reckon you mean,” interrupted Clara, “but I can’t guess what that giant had to do with the small university city across the border.”

“When I said Golias, I meant Golias, which is the name for medieval strolling students, Miss Smarty. Some more reading would do your beauty no harm. Maybe Max will agree with me, it is a wonderful remedy for Weltschmerz.”

“Don’t forget to buy a harp, Florly, since your penchant for show practicing “Easter Bells” on the piano, would not sound so bad on that biblical instrument.” (That was the title of a horrible piece of music, the only one that Florly played by heart.) “But first you have to finish high school.”

Ida gave Clara an intimidating glance and got up. At the door she called, “Clara, come here for a moment, please.” Clara followed her out of the room.

“How could you say such a nasty thing to our sister? She so seldom takes part in such merriment. She caught Max’s frolicsomeness. Flora, in her gentle way, pretended not to have heard your intended-to-be-witty remark, which was not witty at all, but tactless. Don’t you know that Flora, the sweetest of our sisters, has not yet recovered from the influenza, maybe never will, and that she is too weak and sick to attend school? Father hires a private tutor whenever she feels well enough and wants to catch up on her studies. Nobody will care if she finishes high school, all that counts is that she regain her strength. Our parents do what she wants and she wants so little. I had never expected that you could be so rude, you who are always so good-natured.”

Clara, really downcast, answered: “Upon my word, Ida, I didn’t mean to be rude or to hurt her. It was just thoughtlessness. My sense of humor is not as sparkling as Father’s or Max’s. It’s just that we are all in such a strange mood. I think it’s the unbearable heat.”

“I am glad you realize that and don’t think, à la Max, that I am moralistic. I feel guilty too and was perhaps more aggressive than I intended. Please accept my apology and now go in and don’t mention anything, forget about it, and just be yourself – good, so awfully good.”

She kissed Clara who responded with a big hug and both reentered the room.

“Ida, have you changed your mind about playing a sonata with four hands or with me accompanying you on violin or cello?”

“I am not really in the mood.”

“High time to get married. You are becoming old-fashioned, spinsterish and prudish.”

Mother, who entered noiselessly in her soft slippers, said: “Ida is neither old-fashioned nor prudish. She just has better taste in music than you despite your fine technique. I don’t enjoy your vulgar songs. There are so many lovely student songs – both in tune and words. Why don’t you sing some of them for a change if Ida is not in the mood for classics?”

“They are too sentimental and your daughter Mattl needed to be cheered up. I tried to cure her very serious fit of mental sickness. But you, Mummy Rosa, disappoint me by being so touchy. You are a very bad example for Ida.”

Mother left the room as silently as she had entered it, but in a very low voice she said: “Sometimes your insolence knows no limits.”

Ida, in general so composed, lost her temper a second time that day. “Your cynicism is without equal, you brilliant, good-looking good-for-nothing. How dare you talk to our mother like that, and what is worse, in the presence of the children?”

The Flora-Mattl-Clara trio, who earlier showed that they enjoyed their brother’s monkey business better than Ida’s moral philosophy, now sided with oldest sister.

Max felt uneasy, defeated, and with regard to his mother, guilty. He left the room. Ida mastered her feelings again and even produced a faint smile. She knew that Max was looking for Mother to apologize. To find her was not so simple, since she was omnipresent: seemingly simultaneously in the kitchen, cellar, store, and print rooms. To reconcile with her was not difficult – she always made it easy for everybody.

After dinner, Mother put a great platter of apples on the table, which Father had brought from the country. Simultaneously Irma and I started: “Rudiral lalala, Rudiral lalala, never take an apple from that tree.”

Father smiled knowingly and Mother said seriously: “Because you children are being so sassy, you will have no apples.” The Florly-Mattl-Clara trio suppressed their giggling with great effort.

Ida, as usual, saved the situation:

“How about the Kreutzer sonata we rehearsed yesterday, Max? Father would enjoy it and he hasn’t heard us playing together in a long time.”

“Is the air not too polluted?”

“Not anymore,” answered Ida, smiling. “The room has been thoroughly aired out while we were having dinner.”

Arm in arm, they left for the living room. After their performance, Ida said: “Nobody can help but be infatuated with you. You are just irresistible while playing music.”

“I think, if you get married, I will lose the most ideal accompanist – every virtuoso would envy me. I will have to abandon chamber music. You are so sensitive, intelligent, and so unfathomable.”