Feldpost 211, 4 January 1918

My dear ones!

Yesterday I received together letters from Robert, Helene and Kätherl. Today I received a card from Papa from the 26th.

I see from these that my letter has reached you all together in Brüx and I expect your response at any moment. I will write therefore immediately, even though nothing new has happened. About my well-being, do not have any worries. I am splendidly healthy.

Kissing you all,

Paul

Paul Zerzawy was Helene’s nephew, eldest son of her sister Ida. Paul was born in 1895, his mother died in childbirth in 1902 leaving four children under the age of 7. Paul’s father married Mathilde, another of Helene’s sisters in 1903 and in 1904 Käthe, his half sister, was born. Mathilde died in 1910 and it appears that Helene’s mother raised her grandchildren after their mothers (her daughters) died.

When I heard Paul’s name as a child, I assumed that he was a distant relative. I probably felt this way because he was so much older than my mother – he was already 25 when my mother was born in 1921. He was far closer in age to my grandmother, yet he was my mother’s first cousin. He died long before I was born so I felt no connection to him.

Over the past few years, I feel I have gotten to know Paul – he is an integral part of the family story. He saved many letters and documents that have helped me understand all that happened. While she was stuck in Vienna hoping to follow her children to the U.S., my grandmother’s letters to him were more direct and less protective than those she wrote to Eva and Harry. He played an important role in helping her children come to San Francisco and tried his best to help Helene and Vitali follow.

When I was going through the papers in Harry’s closet in 2017, I found a box that looked like it contained a stash of my grandmother’s letters. I was so excited because it promised to be a window into her world. However, I ended up being disappointed because although there were some of her letters, a large part of the box was taken up with correspondence from Paul Zerzawy and his brother Erich that they wrote as soldiers during World War I. It was fascinating to know I had letters that were 100 years old, but they felt very tangential to the family members I cared about. Fortunately, an incredible trove of my grandmother’s letters was still to be unearthed!

Most of the letters from WWI were written in Sütterlin, an old German handwriting style that is impossible to read if you were not trained in it. Unfortunately, the friend who translated hundreds of documents for me does not know Sütterlin. At the end of 2020, I met someone who could translate these letters. Little did she or I know that I would suddenly need some letters translated immediately! I contacted her for the first time in early December and she translated a few letters. By mid-December I decided to write this daily blog and realized that some of the WWI letters were dated in early January. I asked her to translate them ASAP and she was incredibly obliging. Fortunately, these letters were brief and I am able to post the first one today.

Letter written in Sütterlin handwriting.

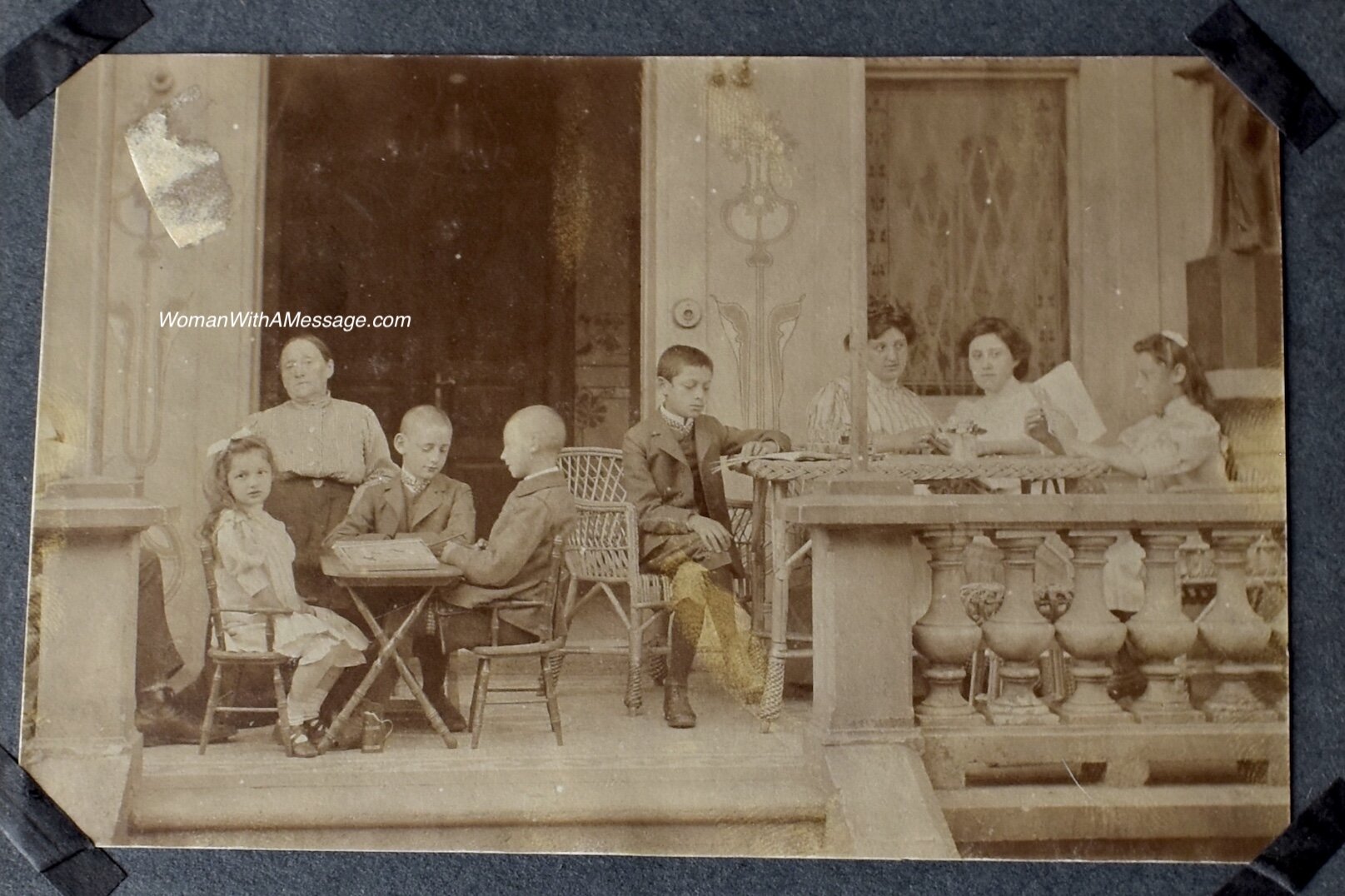

Even a letter as short as this one from January 4, 1918 offers insight into my grandmother’s life and world. In 1917, she had already been living in Vienna on her own for many years. Here she was in Brüx, Bohemia (now called Most in the Czech Republic), apparently spending the holidays with her mother, brother-in-law, niece and nephew.

One challenge in organizing the letters is one that is less a problem today when our computers and phones automatically date things correctly. As we go into a new year, it is sometimes difficult to remember to write the correct year. You’ll notice that the date written on the letter is 1917, but the postmark above is 1918. Easy enough to fix if you have a postmark. Unfortunately the envelopes are missing from most of my grandmother’s letters, so we must rely on context for them.