Link to Family Tree to understand family relationships.

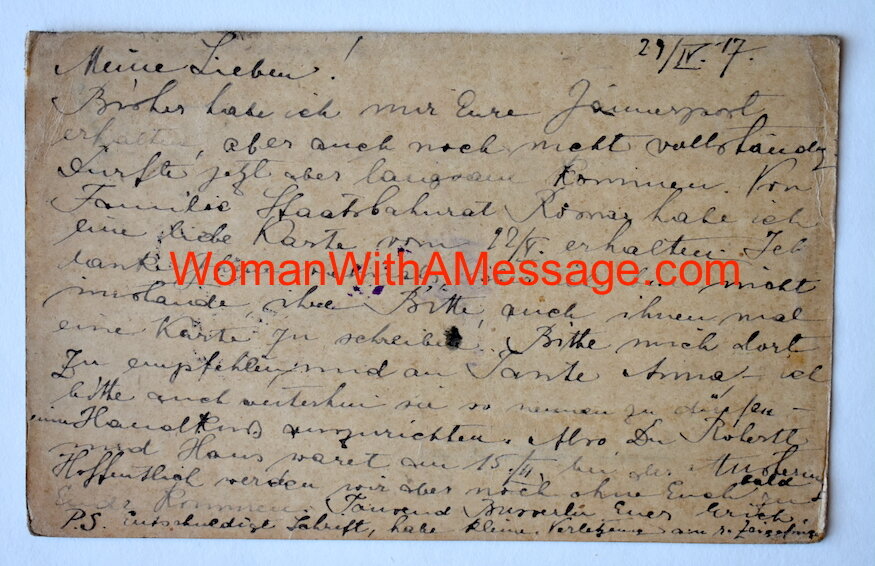

A letter from Helene in Vienna to her nephew Paul Zerzawy in San Francisco:

Vienna, 18 July 1941

Dear Paul! I took stock of things today, but it’s pretty sad. I have written 48 letters to the children since the beginning of the year, but I have received only 10. It is 4 dozen letters: 1) I have not included letters of a different date when they were sent on the same day but in one envelope, 2) letters to you, Hilda, the Zentners, the Schillers, etc. when they were sent to your separate addresses. As you see, my writing business is passive and it must bring up feelings in you about 1870. I am turning to you therefore because I am looking for some sort of resolution. The problem is as you see not coming from me. Of the 10 letters I’ve gotten from the children, the first 7 came closed and they appeared regularly in the first 7 weeks of the year. The other 3 appeared in intervals of 3 months. Since the last 2 were filled with matters of our emigration and made up for the prospect of not getting any mail, we were able to endure this unpleasant situation rather more easily. But since this hope turned out to be fallacious, the lack of letters is appearing twice as painful to me at this point. Do you think that fate has let itself play a bad trick on us? Why? We were so close to getting our goal in life, our happiness and our bliss, come to fruition. We have heard that the children can obtain something in Washington to cause the embassy in Berlin to give us an exit visa. At some point the documents would have to be deposited and this does seem plausible and I don’t think it’s “Bonkes” (a technical term for non-Aryan fairy tales). Please take steps to make sure this happens. It is very very urgent and please let us know if you can’t, where we can turn. About 100 people did get permission to emigrate to Cuba but as we’ve already written, we decided to refrain from such a request because there are new kinds of bother and annoyance with us and apparently doing this requires putting up a certain sum for a deposit. But perhaps you know more about these possibilities over there than the religious community here does. Please Paul, could you take an interest in this and get us some news?

I hope that you are all doing well and I request that you send my best greetings to everybody. Hugging you and greeting you in the best way I can.

Helen

Their July 15 departure date has come and gone and Helene and Vitali are back at the drawing board. They have given up their business and gotten rid of most of their possessions. Having culled to the bare necessities they could take in the few kilos of luggage they were allowed to take on their journey, they now have very few clothes and resources left. They find themselves right back where they began their efforts to emigrate two years earlier. But the paperwork and bureaucracy are virtually insurmountable at this point. There are rumors of ways to expedite the process and Helene places her confidence in her nephew to make it happen. As I read through all the letters, I think about how this responsibility must have weighed on Paul. Although he had been a successful attorney in Europe, in the U.S. he has no resources, credentials, and few language skills to tackle these virtually impossible obstacles. He must have felt helpless and a failure — wanting so much to help his beloved aunt and her husband escape, but being unable to do so.

Helene mentions 1870 as a memorable year for Paul and perhaps herself. Neither had been born yet. Since she is writing this letter on July 18 from Austria which has been annexed by Germany, she is probably referring to a momentous date in European history: Napoleon III declared war on Prussia on July 19, beginning the the Franco-Prussian War. Germany won the war in 1871 and emerged far more powerful. (The only other events I could find that might have been of interest to them both: the concert hall in Vienna that housed the Vienna Philharmonic opened in January and Charles Dickens died in June. In terms of dates of personal importance, Paul Zerzawy’s father Julius was born on September 9, 1870.)