In my April 22, 2021 blog post, I included a story my grandmother had written about her hometown of Bilin (Bilina in Czech), which she entitled The Lion of Bilin, after the mountain that towers over the town. In German the mountain was known as the Borschen and in Czech it is the Bořeň. It was affectionately known as the Lion of Bilin, inspired by a drawing Goethe made of the mountain in the early 19th Century.

As I mentioned in my last post, in May of this year, Czech genealogist Julius Müller took my husband and me to visit Bilina. I had written to the information office the previous year about planning to visit, but received no reply. Upon arriving in Bilina, Julius took us to the Bilina Information Center and mentioned that I was looking for information about my great-grandfather Adolf Löwy, the newspaper publisher. The woman at the desk, Lada Hubáčková, remembered my email and said she had replied but her message had been returned as undeliverable. Lada was very helpful, showering us with information, brochures, and postcards of the town.

My grandmother’s story begins: “Borschen Mountain is located in a valley between the Erz Mountains – the natural border between the Empires of Saxony and Bohemia – and the Bohemian Uplands. It is 538 meters above sea level.”

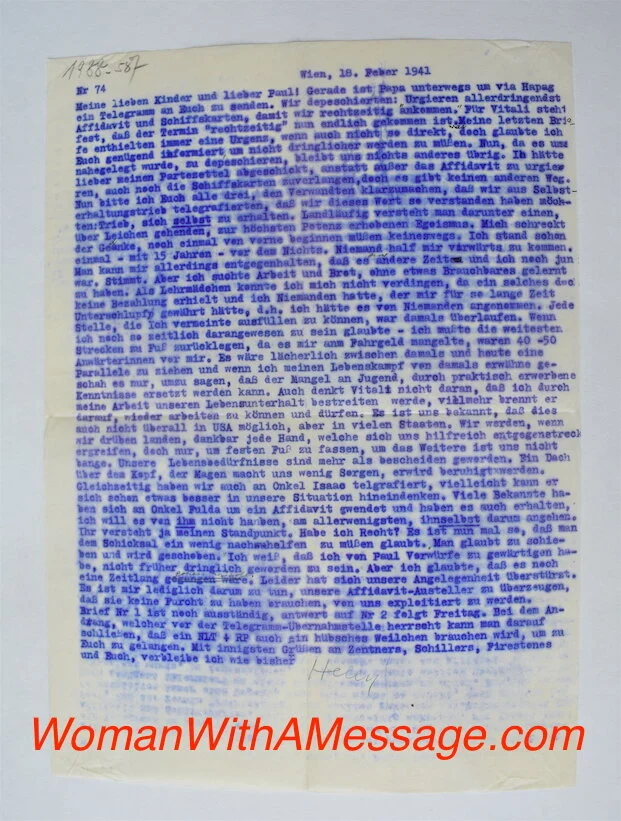

I repeatedly have been amazed by my grandmother’s memory – usually I have been able to corroborate something she wrote by researching in newspapers or vital records. Sometimes I have discovered that she was correct and the record was wrong! At the information center, I found this postcard:

“Aha!,” I thought as I noticed that the postcard said that the mountain is 539 meters high, one meter higher than my grandmother had written. Finally an error - my grandmother’s memory was good but not that good. I mentioned to Lada that my grandmother had recalled learning in school that the mountain was 538 meters high. Lada said that when she was in grade school, she too had learned that it was 538 meters high! Apparently, in recent years the mountain had been measured with modern technology and found to be a meter higher than previously thought.

Yet again, my grandmother’s memory and veracity were flawless!

Julius took us to the cemetery and the spa above the town (a story for another post), where we had a wonderful view of the mountain, which indeed looks a bit like a sleeping lion. I was thrilled to be walking in my grandmother’s footsteps and seeing the places I’d been reading about over the past few years.

My husband and I with the Lion of Bilin in the background.

In the 1980s, my mother and I went to Kauai and saw Nounou Mountain, which is known as The Sleeping Giant. I wonder whether when we saw it my mother recalled stories her mother had told her of the sleeping lion a century and world away?

My mother mimicking the mountain in Kauai