Link to Family Tree to understand family relationships.

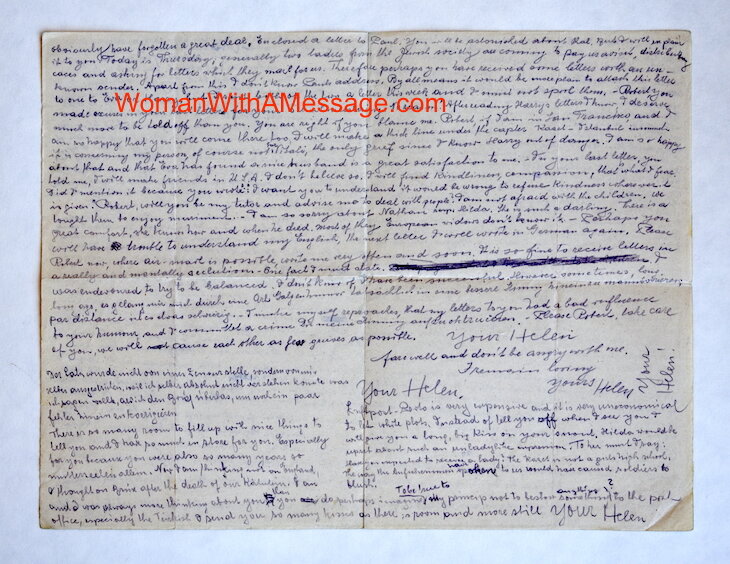

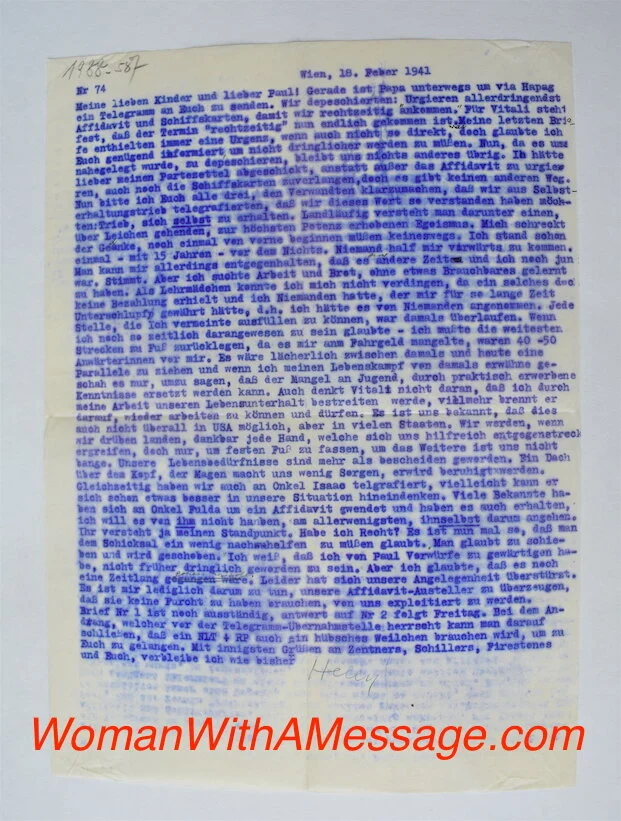

Today letter is from Helene to her nephew Robert in England. It was mostly written in English. The translated German passages are in Italic.

Istanbul, 7 March 46

Dear Robert, My Heaven sent boy! Without you I should be always waiting for letters still, and for some dear loving words. In the meantime, I received plenty of letters from Eva and her husband (he seems to be a nice fellow) and Harry enclosed four always-short letters which proved me that they innermost have not changed. Outside, of course, Harry appears nearly unrecognizable, but not to me. From the flapper Eva became a young woman, her face has not altered.

You wrote me in your last letter: “There is no going back to the past for all of us.” Yes, Robert, I am sorry because there is no road back. Then you continued: “But your children are real. They may have changed - it would be unthinkable that they hadn’t. But that doesn’t offset your relationship. They would have changed in normal times too because they are grown up, and now live their independent life. Is that not right and good so?” Yes, Robert! It is right and good so. Thousand times yes!

Robert, I can’t remember what I have written to you, but from your letters I can see that I must have been crazy. There is a Russian proverb: Look before you leap, and then don’t leap! I will make a variation of it. Think before you write, and then, don’t write! Had I had an idea of it, that you will send my letters which seem to me now to have shown the symptoms of madness I had not sent them away. Dear Robert, don’t mistake me. It is not in the least a reproach, and I didn’t consider it as an indiscretion. I only wouldn’t worry them. Mothers in their love are sometimes egotistical. I rewarded your gentleness, your sympathy, and your affection badly by pouring out all my trouble and cares on you. This letter you can show them; they ought to have knowledge what a beastly mother they have.

There is one excuse for my hoggish behavior. In Vienna Paul was my - I use an expression by Galsworthy - business-nurse. To play the role of a father confessor, he had seldom time for me. There were too many “brothers and sisters.” Since your last stay in Vienna I found out that we have similar related souls and I mean related not in the sense of family or relationship but more of the “elective affinities” [Die Wahlverwandtschaften – a novel by Goethe].

A little scene. You took me out with your car. You, Paul and I had coffee and cakes in a little inn. Before we reached this “Jause Station” [a cafe], you stopped your car when you have seen in a meadow primroses, the first of the year; you gathered them while Paul and I remained in the auto. I watched you and said to Paul: “Look now, Robert has just the same expression on his face as he had as a little boy with (always, please tell it to Hilda) short hair and a straw hat which was like a halo on his head! You gave me this nice looking nosegay and I was very pleased with it, more as by the thought than one from a flower shop. The innkeeper, an old, fine lady, told us how she came to this little coffeehouse, etc, etc, and when we said adieu, she said: “the lean gentleman is your husband, is he not? One can see it immediately because he is so careful.” There were no time and no reason to correct her mistake. I left this little coffeehouse (in English, I know it; but for that term there is no synonym) amused, and flattered of course.

The next day you made another trip in the Vienna Woods in another company. When you came to have dinner with us, you brought me, wrapped in a doe skin, the first violets. That was so nice Robert, so very, very nice of you. The doe skin I stored away, hoping to give it back to you. It is gone with all our things, but not the recollection of how I happened to keep your doe skin. It is unbelievable what little events are stored away in our brains and how dear those little intermezzi can be.

Before I fell in the melancholy way, I lived more in the present and in the future, and here I seek refuge in the past. On the delay of my departure I am not quite without guilt. Had I written to you about the money affair, things would have been altered. But I didn’t know in which pecuniary condition Eva and her husband are living, I know Harry a soldier. Before the Joint Association asked for the money, every delay seemed to me a new punishment, but I comforted myself saying: The only good thing in this bad job is that the children have not to pay for my passage. My wits began to turn once I knew they have to pay for it, and I stayed here so long I can say Lugsi [?] voluntarily.

Robert, you mentioned in your last letter that I told you that I am reading Shakespeare, but I hope you will not have expected letters in Shakespearean style. I am glad to receive letters in the English language. It enlarges my knowledge of it and compels me to think in this language. Reading letters is so much easier and more agreeable. I am astonished that you write German correctly still, while my children obviously have forgotten a great deal.

Enclosed is a letter to Paul. You will be astonished about that. But I will explain it to you. Today is Thursday, and generally two ladies from the Jewish society come to pay us a visit, distributing cakes and asking for letters which they mail for us. Therefore perhaps you have received some letters with an unknown sender. Apart from this I don’t know Paul’s address. By all means it would be more plain to attach this letter to one to Eva or Harry, but I sent both of the two a letter this week and I must not spoil them.

Robert, you made excuses in your last letter for your acting like a school master. No reason! After reading Harry’s letters I know I deserve much more to be told off than you. You are right if you blame me. Robert, if I am in San Francisco and I am so happy that you will come there too, I will make a thick line under the chapter Kassel - Istanbul insomuch it is concerning my person, of course not for Vitali, the only grief since I know Harry is out of danger. I am so happy about that and that Eva has found a nice husband is a great satisfaction to me.

In your last letter, you told me I will make friends in USA. I don’t believe so. I will find kindliness, compassion, that is what I fear. Did I mention it because you wrote: “I want you to understand it would be wrong to refuse kindness wherever it is given.” Robert, will you be my tutor and advise me to deal with people? I am not afraid with the children. We taught them to enjoy merriments. I am so sorry about Nathan with respect to Hilda. She is such a darling. There is a great comfort she knows how and when he died. Most of the European widows don’t know it. Perhaps you will have trouble to understand my English, the next letter I will write in German again. Please Robert now, where air mail is possible, write me very often and soon. It is so fine to receive letters in a really and mentally seclusion. One fact I must state, I endeavored to try to be balanced. I don’t know if I have been successful. However sometimes, long, long ago, I succeeded in by using a kind of gallows humor by getting myself in a better mood, but long distance, it is somewhat difficult.

I make myself reproaches, that my letters to you had a bad influence on your humor and I committed a crime to impose upon you. Please Robert, take care of you, we will cause each other as few griefs as possible.

Your Helen

Farewell and don’t be angry with me....loving

Yours HelenThe sentence was not crossed out by any censorship agency, but rather I did that myself because I myself absolutely couldn’t understand what I wanted to say when I read over the letter to try to correct a few mistakes.

There is so many room to fill up with nice things to tell you and I have so much in store for you. Especially for you because you were also so many years so very alone [the mother of all German words for ‘loneliness’] Now I am thinking not on England, I thought on Brüx after the death of Kätelein. I am and I was always more thinking about you than you perhaps imagine. To be true to my principles is not to bestow anything/something to the post office, especially the Turkish. I send you so many kisses as there is room and more still

Your Helen

Airmail postage is very expensive and it is very uneconomical to leave white space. Instead of tell you off when I see you I will give you a long, big kiss on your snout. Hilda would be upset about such an unladylike expression. To her must I say: Have you expected to receive a lady? The Kazet [concentration camp] is not a girls high school. The way the female guards have spoken to us would have caused soldiers to blush.

One thing that has become clear is how proud and independent she was. In many respects, that is a great thing. However, her letters show us she was uncomfortable asking for financial assistance from family members, which may have prevented her and Vitali’s safe passage from Vienna before it was too late. In this letter too, she is sorry she hadn’t asked for monetary assistance earlier, assuming that the bureaucracy of the Joint would provide the assistance she needed.

You can see that Helene made a point of filling every inch of space on the paper, commenting on the cost of postage and the desire not to waste a penny. She made sure to include many loving signatures and endearments, not wanting to let go of this connection to her past, present, and hopefully future.

I continue to be amazed at how much was shared across the oceans. Letters traveled from Istanbul to London to San Francisco so that everyone knew what was happening with their loved ones abroad. This turned out to be a happy practice for me, since I would not have this letter otherwise.

Despite all that Helene has been through, she still has great empathy for others. She feels that she and Robert are kindred spirits. She lovingly recalls things that Robert did as a child and young adult. She grieves with his many losses and current solitude: his half-sister Käthe died in 1918 at the age of 14 and Robert lost his own mother before he was three and his step-mother/aunt when he was 10.